College Grief: Finding A Support Group of Dead White Men

/ Coping with Grief : Litsa Williams

There is this Tom Petty quote plastered all over the internet about college. “I've learned one thing, and that's to quit worrying about stupid things. You have four years to be irresponsible here, relax. Work is for people with jobs. You'll never remember class time, but you'll remember the time you wasted hanging out with your friends. So stay out late. Go out with your friends on a Tuesday when you have a paper due on Wednesday. Spend money you don't have. Drink 'til sunrise. The work never ends, but college does...”

I finished my freshman year of college like most other freshmen. I followed plenty of Tom Petty’s words of wisdom. I hung out with friends. I stayed out all night. I took sailing classes. I spent money I didn’t have. I played drinking games. I took naps.

I went home for the summer. My dad died.

When I came back for sophomore year, I didn't feel like most other college sophomores. Everyone else was picking up where they left off. Friends, parties, boyfriends, drinking games, movies, more drinking, and more naps. I wasn't ready to settle back in.

I worried about how I would readjust to this world, and how my friends would readjust to me. Strangely, my grief seemed to make sense to other people. Most people couldn't fathom losing a parent so my pain didn’t surprise them. No one expected me to get over it, because we were all 19 years old and no one could imagine getting over it.

This didn’t change that I felt alone in my loss – supported, but alone. I still knew my grief made people uncomfortable – who wants to think about death and grief when you could think about . . . pretty much anything else? My questioning of God, the afterlife, my purpose in life, intertwined with a lot of tears and suffering just didn’t mesh well with beer pong and theme parties.

So instead of burdening friends, I signed up for creative writing classes. I would write about a life that I could barely believe was my own. I wrote about feelings I had not felt comfortable sharing with friends. I wrote about my pain. I wrote about my confusion about the world. I didn't care if it was "good" or not. I wrote because it made me feel better.

Soon we had to pick and read a poem we had written to the class. I dreaded the potential looks of discomfort. I found a poem that seemed light. “We buried my father in his nicest tie; neck restrained like a chained dog . . .”. Two lines in and I could feel an uncomfortable silence had fallen over the room. I forced my way through, line by line talking about my father’s funeral suit, my mom’s panic when she realized she had forgotten to bring shoes to the funeral home. I pushed through to the last lines, “don’t worry, said the funeral director, no one will see his feet”.

I waited for someone to laugh. The absurdity of it was funny. That was why I decided to share it. It was light! It was funny! No laughs. Plenty of uncomfortable silence and lack of eye contact, but not even a giggle. I didn’t read any more poems about death or grief after that.

Thus ended my career with creative writing. I signed up for philosophy classes and religious studies classes. I would try to make sense of a world that clearly made no sense.

Heidegger distinguished our existence as “being-towards-death”. I thought about this constantly during the end of my sophomore year of college. Our awareness of death is what distinguishes our lives. Before philosophy I had not been able to make sense of why I was not interested in the things that used to interest me – I didn’t understand how so many people were content with life and I was completely unsettled. I wrote it off to grief but it was not just grief in the way I had understood the word. It was not just the pain of my loss and missing my dad, but the shift in my understanding of my own life. It was my existence as “being-toward-death” – acutely aware that life can change in an instant, that nothing is permanent or guaranteed, that the things that seem meaningful can suddenly seem meaningless.

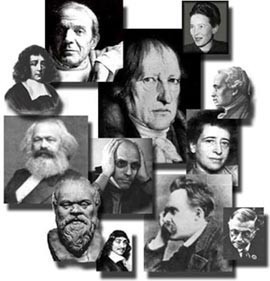

I read rational arguments about death – what is death, why we should fear death, why we should not fear death, why we should think about death, why we should not think about death. I thought about life and identity. I read and I read and I read. I didn’t talk about my dad’s death directly (creative writing had taught me that was not a good plan) but I talked about all the things it made me question about my existence. No one looked at me like I was crazy, or avoided eye contact. Philosophers had been grappling with these same questions for thousands of years. I found myself a 19-year-old college sophomore in a grief support group of dead white philosophers, and somehow it helped.

I was initially frustrated that these old (dead) white men were so determined to talk about death and the authentic life in terms that felt so devoid of emotion. But as time went on I was finding the emotion hidden in their philosophy. Levinas’s critic of Heidegger seemed to me to come from a place of deep understanding of grief and the death of another. I found people like Kierkegaard, who were affirming emotions. Grief is rooted squarely in emotion (the red-headed stepchild of philosophy). I could not blame them for keeping their distance. With these people, I could write about, and talk about, my questions of existence and get a degree doing it. I could forgive them for not being more direct about their pain.

Cicero once said, “To philosophize is to learn how to die”. I did not cite this when people questioned what I would ever “do” with a philosophy degree, though I probably should have. What Cicero, Heidegger, and countless other philosophers remind us is that only by learning to die -- by facing our death, “being-towards-death”, recognizing the fear and anxiety of our own mortality -- that we learn how to live an authentic life. This is not as abstract as it sounds. Really. When we grieve we reassess and reevaluate. We reconsider our priorities. We question what we thought we knew as fact. We accept that our time here is oh-so-finite. We become aware of our radical freedom to create the life we want to live.

These philosophers were not the support group I imagined, but I am glad I found them. By the end of college, they even had me valuing the words of Tom Petty again.

I am not the only one who has found support in philosophy -- Apparently, it is good for more than just college grief. Check out this Washington Post article on philosophical therapy: https://articles.washingtonpost.com/2011-08-22/lifestyle/35272176_1_mental-health-counselors-diagnosis-of-mental-illness

Had your own experience with grieving in college or using philosophy to cope with grief? Leave a comment. Seriously. We love comments!

We wrote a book!

After writing online articles for What’s Your Grief

for over a decade, we finally wrote a tangible,

real-life book!

What’s Your Grief? Lists to Help you Through Any Loss is for people experiencing any type of loss. This book discusses some of the most common grief experiences and breaks down psychological concepts to help you understand your thoughts and emotions. It also shares useful coping tools, and helps the reader reflect on their unique relationship with grief and loss.

You can find What’s Your Grief? Lists to Help you Through Any Loss wherever you buy books:

Alexandra Seago February 24, 2019 at 7:42 pm

I’m a senior in college finishing up my last semester, and my grandpa passed away just about 2 weeks ago. The hardest thing for me so far has been having to jump back into my old routines and keep moving on after coming back from the funeral. I know things will get easier with time. I am working on being patient and trying to let myself feel everything and heal while working hard on finishing my degree. It has not been easy. But I am thankful for my friends here. ❤️

Taelor March 13, 2013 at 1:10 pm

BINGO! When I was between the ages of 10-12 my grandma, grandpa, and dad all died. And those are some pretty formative years, much like the ones spent in college. What you said above is exactly how I have felt, but lacked the words to articulate. All of my adult life I’ve been a pretty confident person and I truly believe that it comes from “being-towrd-death,” as you and Heidegger put it. Becoming so intimately acquainted with mortality at a young age really makes you appreciate that life is, in fact, short; you do only get one go-round; you shouldn’t sweat the small stuff and every other cliche that old people lament and young people roll their eyes at. You and I, we know it through and through, we’re going to die. And knowing that really minimizes the compulsion to live anything other than an authentic life. There’s your silver lining.

Litsa March 13, 2013 at 7:42 pm

Thanks Taelor- it is always nice to feel we are not alone in our experience! It can be so hard (even controversial) to talk about the silver lining of a death, but I absolutely agree with you. I would trade my approach toward life (and death) any day to have my dad back, but since that is not an option I try to value and appreciate the ways it made me the person I am. I can’t imagine going through the loss you did before high school – your perspective is admirable.