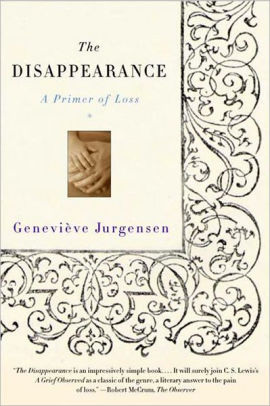

The Disappearance: A Primer of Loss

/ Books, Movies, and Music : Litsa Williams

Written nearly twelve years after her four and seven-year-old daughters were killed in a car accident in France, Genevieve Jurgensen’s The Disappearance allows us a glimpse into her relationship with these two little girls in the years since their deaths.

Written originally as letters to a friend she met several years after the girls died, she begins by explaining, “you never knew our daughters, neither did you know me as I was when they were alive. I will have to tell you everything . . .” By the end of the book, I was overwhelmed by the connection I felt to Jurgensen and her girls, despite the non-traditional methodology to her story. There is no straightforward narrative, no advice, no self-help, no theories about grief and loss - just Jurgenson's personal experience in letters.

What first distinguishes this book from other grief memoirs is the rejection of a linear account of the death of her daughters and the subsequent years. Jurgensen dedicates only two short letters in The Disappearance to the year following Elise and Mathilde’s deaths, and give us very little insight into her experience during that time.

What she gives us instead is an intimate look at how the loss of her daughters continues to shape her life twelve years later. Discussing the experience of writing these letters, she asks many questions, “the further I get from the 30th of April 1980 [the date of her daughters’ deaths] in this account, the more I suffer . . . I resent the past, which was so hard to live, for pulling me backwards. I resent you for not having been there then.” In later letters she questions why she should bother “moving backwards” to revisit these events.

Though Jurgensen does recount many events for us, it rarely feels like she is moving backward; her letters are as much about her life today as they are about her experience twelve years ago. Her inability to give a chronological account of events may be frustrating for some readers, but it rings true to the experience of grief.

As a griever, you connect with Jurgensen’s attempt to reconstruct weeks or months that are a blur yet are intertwined with memories that are as vivid as yesterday. There are many times you feel Jurgensen trying to work through the details sequentially but finding that their connection to the present is more important than their chronology. I was left feeling not that she was revisiting the past but rather that she was showing us how this loss is both part of the past and the present.

Jurgensen articulates some of the most common experiences faced after the loss of the child. In a letter from June of 1993, Jurgensen reflects on her isolation from other mothers. She says, “I was not like other mothers . . . if another woman wanted to talk to me, I had only two options: a bright façade, which devastated me, . . . or a truth that was socially unacceptable (‘these are my younger two children. The elder ones died four years ago’). I would always be out of place.”

She describes being asked how many children she has and feeling unable to answer– feeling she betrays her daughters if she does not include them while dreading the reaction she will face if she has to explain the deaths of two children.

Jurgensen includes the perspective of her two children born after Elise and Mathilde. These children watch her closely whenever this question is asked – waiting for the answer and scolding when she answers two instead of four.

The Disappearance shows us a family in which the little girls who died are deeply connected to the siblings born after their deaths, Elvire and Gauthier. Jurgensen tells us how Elise and Mathilde were always discussed freely, never hidden from her two younger children.

When Elvire asks her mother when they first told her of the death of her sisters, Jurgensen cannot give her an answer. As parents, they had, “never hidden anything from [Elvire] but one day she just understood. Just like that.” While so many parents struggle with how to explain the death of a child to younger children, we never get the sense that Jurgensen worried herself with how and when she would have this conversation. Rather, Elise and Mathilde were always a presence in the family.

Jurgensen tells us about the day of the accident, receiving the call from her brother-in-law with the news of their deaths, and going to the hospital. We learn very early in her letters that she chose not to see her daughters at the hospital; that “you would have had to drag [her] there with a tractor”. It is not until many letters later that she shares her regret around this decision – the guilt that she could not find the strength to be with them; that she “stayed on [her] chair like a lump”. Though the circumstances may vary, her regret will ring true with so many grievers who fixate on those things they wish had been different but can’t change.

Jurgensen shares little about her husband in her letters, and I found myself wondering whether he had gone to see the girls, or if this was a regret they shared. Sadly, we get little detail of her husband’s experience. We know their relationship survived the loss of these two children but we learn little more than that.

The professional in me, knowing how many marriages do not survive this type of loss, did wish for more about their relationship. Jurgensen explains, perhaps knowing her reader will wonder, that she does not include her husband as an effort to protect his privacy.

Though writing twelve years later, what makes Jurgensen’s letters especially powerful are the specific images and words she recalls from the time of the accident, and how deeply connected they are to the present. She describes a statement made on the day of the funeral by an acquaintance: “you will see, you can get used to anything.” She goes on to describe this as the “most simple, true, brutal and perceptive thing that anyone said to me at the time . . . either a message of hope or of crushing contempt for human nature.” Not only did this statement ring painfully true as I read it, but it was clear how deeply connected it is to Jurgensen’s perspective. The Disappearance does not read as a memoir about “recovery” but one of getting used to a new life.

Palpable in Jurgensen’s letters is the knowledge that they are as much for her as for anyone else. As readers, we are just lucky Jurgenson has allowed us access to this simultaneously painful and beautiful creation that came from her tremendous loss.

I closed this book thinking of these two little girls as the four and seven-year-olds they were when their lives were cut short, then as the seventeen and twenty-year-olds they should have been when these letters were written, and finally as the women they should be now- older than Jurgensen herself was when these letters were written. I was left wondering about the person Jurgensen is now and what her relationship with Elise and Mathilde is today.

We are never entirely sure what Jurgensen’s goal is for this work (if there is a goal at all). What's clear is that a hope she articulates at the end of a letter from June of 1992 seems fulfilled: “I am trying to make you concede that Mathilde and Elise were just as alive in Auteuil the day before yesterday as their brother and sister were in the Gardon yesterday. There is no difference between the four of them, except simply that two are dead and the other two are alive. That is a fact.”

Who should read this book? Anyone who is looking for a glimpse into the experience of a mother who has lost her children and the lifelong grief that comes with the loss. Who should skip it? Someone who is looking for a book giving specific advice on coping with the loss of a child.

For more recommendations for books about grief, check out the following articles:

- 32 Books About Grief

- 32 (More) Books About Grief

- 64 Children’s Books About Death and Grief

- Grief in ‘Looking for Alaska’: A Grief Book Book Review

- Six Books for Grieving Teenagers

Subscribe.

We wrote a book!

After writing online articles for What’s Your Grief

for over a decade, we finally wrote a tangible,

real-life book!

What’s Your Grief? Lists to Help you Through Any Loss is for people experiencing any type of loss. This book discusses some of the most common grief experiences and breaks down psychological concepts to help you understand your thoughts and emotions. It also shares useful coping tools, and helps the reader reflect on their unique relationship with grief and loss.

You can find What’s Your Grief? Lists to Help you Through Any Loss wherever you buy books:

Nicola Martin October 15, 2017 at 5:39 am

I am currently writing ‘bereaved mother about town’ and really get how hard it is to write in a linear style. John is loved in the present tense and will always be one of my three children.

Nicola Martin October 15, 2017 at 5:39 am

I am currently writing ‘bereaved mother about town’ and really get how hard it is to write in a linear style. John is loved in the present tense and will always be one of my three children.

Dani July 5, 2015 at 3:55 pm

I’ve been meaning to read this book ever since I heard an excerpt from it on This American Life many years ago (https://www.thisamericanlife.org/radio-archives/episode/144/where-words-fail?act=1). It was so honest, beautiful, tender, loving, and heartbreaking that I’ve never forgotten it. Somehow I never got around to reading the full book, but I am definitely motivated to after reading your review, thanks for the reminder!